M.018 Batman vs Clark Kent

AI Work Part 3: AI Doing in context

You are reading Molekyl, finally unfinished ideas on strategy, creativity and technology. Subscribe here to get new posts in your inbox.

“Vibe” has become one of the defining terms of the GenAI wave. It started with Andrey Karpathy describing on X how he “vibe-coded” by instructing AI to do coding work with natural language, and other variants like vibe marketing, vibe designing, vibe writing and vibe working quickly followed.

While the buzz and hype around vibe working are real, the term also points to something deeper about how AI has and will change work. It rocks ingrained assumptions about the efforts and skills needed to pull off many types of knowledge work, and what is possible to do in a given time. As it allows us to tackle a range of complicated problems without the time and efforts required to learn the underlying craft.

Suddenly, I can turn abstract ideas into a working realities across so many domains instead of just storing them in my drawer of good intentions. Create functional software tools without knowing how to code. Create videos and images without having to fiddle with cameras, actors and lights. Make music without having to refresh my guitar skills. Or as Karpathy put it in the mentioned X-post: you can “[…] just see stuff, say stuff, run stuff, and copy paste stuff, and it mostly works”.

When I “vibe away” with AI tools, I therefore feel a bit like Batman. A regular guy who just discovered a secret basement full of advanced equipment allowing him to tackle problems he normally couldn’t.

But my good vibe-work vibes get a hit every time I am reminded of what the real craftsmen can pull off with the same tools. Like my colleague Alexander Lundervold, mathematician, software engineer and professor of AI. When he vibes with AI, he becomes Superman. Capable of lifting buildings and flying. And I am reminded that Batman is just a regular guy. Fancy tools, yes. Superpowers, no.

While there are many skilled people like Alexander who have turned into real superheros with AI, it also seems like many haven’t. Especially if we look beyond programming and coding. They keep their suit and glasses on, and stay in Clark Kent mode. While people high on curiosity and openness, and low on deeper knowledge and judgment, jump into the batmobile and vibe away.

Non-designers pump out marketing campaigns for their companies while many truly skilled designers stick closer to their craft. Non-writers churn out posts, articles and books while skilled writers limit their AI use to fixing grammar. Non-musicians pump out Spotify hits, while trained musicians tinker with new songs in their studio.

I don’t have any data to back it up, but there seems to be a pattern. Where many of the people who would benefit most from doing stuff with AI, those with the domain expertise and deeper skills in a field, are holding back, while happy amateurs are leaning in.

Which begs the question: Why is this happening?

The answer, I think, has less to do with technical capability and more to do with something else: execution control. Who’s actually making all the thousands of micro-decisions that turn a prompt into a finished product, song or image?

The trade-off between speed and control is at the heart of doing with AI, and is more than just a security question. It also a question of who can do what, who wants to do what, and who’s building vs degrading key capabilities.

To understand the potential implications of this pattern (assuming it’s true), we need to take a step back, and look at what “doing” with AI really means.

What Doing Actually Means

Doing refers to the act of performing an action or carrying something out. It represents the transition from intention to reality, from planning to implementing, from knowing to applying. The difference between having the big picture direction, and operationalizing it in many smaller decisions.

As I noted in my first post in this little series, it’s often hard to practically separate doing from the other main component of work, thinking.

But it makes sense to give it a try because the two require different forms of control. With thinking, as I discussed in my previous post, the key question is who maintains cognitive agency. Is it the human or the AI’s reasoning that guides the process? With doing, the key question is who maintains execution control. Whose methods and judgment shape all the micro decisions that need to happen for work to actually get done.

Maintaining execution control is therefore more than just reviewing and quality checking any output. It’s also about directing the micro decisions that must be made, to intervene and correct when needed, and to understand the process steps well enough to be able to evaluate any final results.

High execution control means that discretion over these factors lies with a human. Low execution control means that many such decisions are outsourced to an AI.

The Four Modes of AI Doing

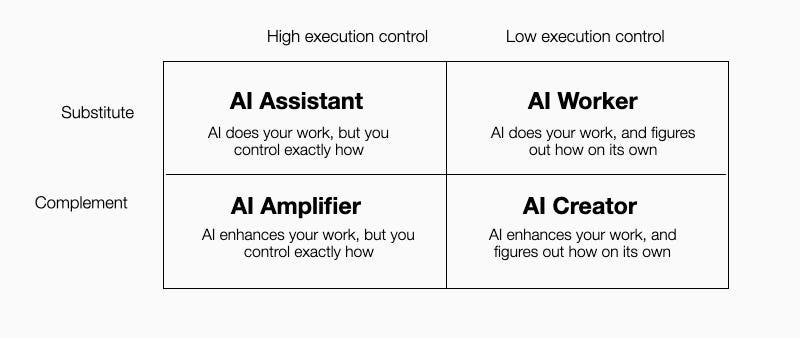

If we combine the dimension of execution control with the substitute/complement dimension I also used when exploring AI thinking, we get a stylized map over different modes of AI doing.

The map shows that doing with AI varies depending on whether AI is substituting or complementing human doing, and whether humans maintain high or low execution control over the implementation process.

The two high control modes are more akin to doing work with someone you micromanage, while the low control modes are closer to giving someone the what and let them figure out the how. It’s where the vibes are strongest. Let’s look closer at each of these modes in turn.

AI Assistant: Controlled Delegation

The first variant of AI doing is to use it as an assistant. Here a human delegates specific execution tasks to AI while maintaining control over how work actually gets done. The AI becomes a capable assistant that follows your detailed instructions. You could have done the work yourself, but chose to hand off the execution to an AI. Much as you would have done it.

Ask an AI to write emails using your specified tone and structure, craft a report following specific steps, or format your scattered meeting notes into a polished summary matching your preferred template. Any delegation where you both maintain control over the execution, and use it in ways that substitute for your own doing, would fall in this category.

Since the actual doing is controlled by a person, the value depends on what that person brings to the table. Someone with deep domain expertise and precise communication skills will get far more value using AI as an assistant as they know exactly what they want and how to direct the AI.

The benefit of using AI as an assistant is to scale your unique approach without compromising quality. The cost is upfront investment in specifications and process design. More control, less efficiency.

AI Amplifier: Enhanced Execution

The second mode of AI doing is to have it complement or amplify your own skills and knowledge, like handling tasks you normally couldn’t or wouldn’t do yourself, while you stay in control of how these tasks are executed.

The key is that the user should have the ability to control and direct the process, despite lacking the capabilities to do it themselves. A good writer can evaluate suggestions of an AI editor or see when an AI proofreader has amplified the text, even if they couldn’t do either task as well themselves. A designer with strong visual sensibility but weak coding skills can evaluate whether the implementation of their design in code aligns with their vision, even if they couldn’t code it up themselves.

The value of the AI amplifier mode thus comes from amplifying your own skills and filling in your gaps. But to remain in control of the doing, you must also be able to direct and evaluate the processes and steps you can’t do yourself.

For some tasks, like the example with the designer, this may be straightforward. For other tasks, much harder because the competence holes are bigger. The cost of the AI amplifier mode is therefore the time spent on giving proper delegation, and the time spent trying to control the tasks you couldn’t do yourself. More control, even less efficiency.

AI Worker: Autonomous Execution

The third variant is AI worker mode, where an AI substitutes for human execution with minimal human control. Here you specify the what, and the AI figures out the how. This is the mode closest to delegating work to a human worker.

Compared to using AI as an assistant, the efficiency of the AI worker mode is striking. You don’t need to specify details upfront. You can just follow the vibe of your vision, give the AI a high level task, and jump straight to evaluating results. And unlike assistant mode, the value it can create is less constrained by your own (lack of) expertise. The AI uses its own capabilities to figure out the how, while the human can focus on the vibe.

This creates a massive scaling potential as we can do work that normally requires humans, and work that until now hasn’t made sense to assign to humans at all. Like updating a competitor analysis every week, and turning the key updates into a lively podcast for the CEO consume on her way to work every Monday.

For valuable but non-critical work, outsourcing execution control to an AI might be fine. For critical work, it can be much more risky. Because what if the AI gives misleading updates to the CEO? Or what if your automated customer service chatbot operationalizes your instructions to “make customers happy” by giving away your products for free?

While domain knowledge and expertise matter less when we delegate more to an AI, they matter more to assess and understand the possible risks of delegating a given task. The more complex, autonomous and hidden the AI’s execution process is, the more challenging it gets to evaluate the process from only observing the end result. And the greater the value of domain experience in understanding the hidden risks.

Deep domain expertise therefore helps assess risks, like knowing when automated competitor analyses might mislead a CEO. Users with less execution expertise are more likely to trust AI blindly. Because they don’t have an alternative.

The value of the AI worker mode therefore comes from efficiency and scalability, while the costs are associated with the risks from low execution control. In some areas this risk will be low, in others it will be high.

For tasks where you can accept variation in quality, or where you deliberately want to explore approaches different from your established methods, the efficiency of an AI worker is gold. For critical tasks that matter, it might very well be a gamble to delegating it to an AI. Less control, more efficiency.

AI Creator: Collaborative Execution

The final mode is when AI works as a creator that complements your own skills and capabilities with significant execution autonomy. The result is a collaboration where both human and AI make distinct contributions to create outputs neither could produce alone.

When I use AI to generate images for presentations, I usually start with an abstract and incomplete vision capturing the essence of an idea: “I want an image of a rat in a Barbour jacket”. The AI interprets my prompt, and makes countless micro-decisions about composition, lighting, style, and detail to produce some images. The result might match my vision, or it can diverge completely. I then adjust my prompts based on what I like and don’t like, the AI takes another pass, I adjust again, and so it goes. The final work becomes a genuine creative collaboration, that I vibed my way into creating. The execution control was in the hands of the AI.

The value of using AI as a creator comes both scale and execution diversity. Higher experimentation rates, more creative solutions, and lower costs. One highly capable person with AI can run experiments at a scale that would require a full studio of workers only a few years ago. And when the AI brings different capabilities than yours to the table, the results are often something neither could achieve alone.

But AI creator mode also carries risks from ceding execution control. The AI might take work in unanticipated directions, contributing elements you wouldn’t have chosen. Or being too inspired by something or someone, without you knowing.

So even if AI creator mode is less dependent on your own capabilities, having strong domain expertise and execution skills still matters here too. Good taste and judgment gives an edge when evaluating, curating and selecting among output. It allows you to know what to keep, and what to toss. And it gives a better understanding of the involved risks.

The best AI image or video creators are people with good taste and visual literacy allowing them to direct an AI toward their vision through iterative refinement. Lucky novices less so. But still, the less control, the bigger the efficiency.

The vibe paradox

The walk-through of the four modes highlights a fundamental trade-off between execution control and efficiency in AI doing: It’s increasingly hard to achieve both at the same time.

Less skilled users will more often choose efficiency over control. They can use all the shiny equipment in the bat cave without understanding their full capabilities or associated risks.

Many skilled users on the other hand, seem to lean more towards higher execution control. Their expertise makes them aware of all the ways things could go wrong if giving up control, and they likely also have stronger preferences for how specific details should be executed.

They could lean in and use AI to push their skills from high to superpower. Like many developers already do, fluently and deliberately jumping between modes, based on what is right for the task. Spot critical risks and make deliberate decisions about them, and know which corners can be cut and which can’t.

But across fields, my guess is that the expert craftsmen and women are relatively less likely to do so than the happy amateurs. Which points to something of a paradox.

The skilled workers would get higher benefits of the low control vibe modes than the happy amateurs, but shies away from these modes because of their deeply held skills. They see more of the risks, and need stronger proof that AI execution is reliable before ceding control. The red outfit and cape is there, but remain hidden under Clark Kent’s suit and glasses.

At the same time, less skilled people vibe away, enjoying all the cool tools in the bat cave. Running around solving problems they never could before, stretching the efficiency potential of AI until they have solid proof that something wasn’t a good idea. With less understanding and concern for the consequences of ceding execution control to an AI.

The battle between the two could be Bateman vs Superman. More often it’s likely Batman vs Clark Kent.

How the battle actually plays out, is however more uncertain. The vibe worker’s choice to prioritize efficiency over control can be reckless since the efficiency gains could implode from the underlying risks. But it may also be (implicitly) strategic because less skilled “vibers” could succeed precisely because the speed and efficiency allowed them to move and build traction faster than their more conservative and skilled counterparts. Time will tell which one is more likely in each case.

If, however, more of the Clark Kents decide to enter a phone box and change gears, the outcome quickly becomes more predictable.

The Learning Trap

Below the dilemma of the vibe paradox lies another, more subtle and personal trade-off: the more we cede control of the execution to an AI, the less capable we might become using AI for the tasks that require greater human control.

This is because the knowledge and skills required to be good at delegating and steering an AI, or assessing the associated risks or noticing important nuances, are developed and maintained from, you guessed it, doing things ourselves.

When we consistently let AI figure out the how, we don’t develop or maintain our own execution knowledge and skills. We don’t learn which methods work better for different situations. We don’t build the pattern recognition that lets us precisely specify process steps and nuances. We don’t develop the personal taste that lets us direct collaborative execution effectively.

A worry is that this pattern emerges gradually and invisibly. When we are getting more work done than ever, these changes are harder to spot.

For the batmans primarily delegating execution control to AIs, they might therefore never develop the deeper process and task understanding that would allow them to truly benefit from AI assistants and amplifiers, and fluidly jump between modes based on which one is best for a task. They get stuck with their shiny tools in low control modes, without a path to gain real superpowers themselves.

For the Clark Kents that do turn into supermen when the situation demand it, too much vibing may also have its consequences. Over time it might erode the very thing that gave them superpowers in the first place.

Using AI for doing tasks is therefore more than a question of balancing execution control with efficiency. It’s also a question of developing or degrading our future execution capabilities.

Closing

While many Clark Kents are still debating whether it’s safe to fly, the Batmans are already out there using their shiny new tools to solve problems. If its primarily the less skilled that embrace AI first and move faster, systems might end up being shaped around their speed rather than around the rigor of the Clark Kents.

AI capabilities develop at lightning speed, implying that moving fast with questionable fundamentals will often beat moving slowly with safe and sound foundations. The efficiency gains of the low control AI modes are immediate and highly visible, while their potential risks are often more hidden.

The learning trap makes this pattern self-reinforcing. The more the Batmans vibe, the better they get at vibing. The more the Clark Kents wait for proof of safety, the more comfortable they might get staying on the ground.

So how can the skilled workers approach this dilemma? The answer for sure isn’t to abandon all caution and vibe everything. Execution risks are often real, and expertise exists for good reasons. But I also don’t think the answer is to wait for AI to become perfectly reliable before ceding any control. That day may never come. And even if it does, the systems might then have already been redesigned around the people who moved faster.

A better balance is to do as the top developers of today. Switch between modes. Use their domain expertise to know when to stay Clark Kent, and when to become Superman. When to use your expertise to vibe strategically and take calculated risks where speed matters and consequences are recoverable. And when to maintain control and not compromise on quality and risks.

But unless the Clark Kents of this world occasionally enters the phone booth, it will be a battle between Batman and Clark Kent. And then it might be the Batmans that will build the future. With tools they might not fully understand, in ways that could reshape what expertise even means tomorrow.