M.016 The elevator operator’s dilemma

AI Work Part 1: AI work in context

You are reading Molekyl, finally unfinished ideas on strategy, creativity and technology. Subscribe here to get new posts in your inbox.

One of the classic books exploring the impact of technology development on society is Aldous Huxley’s “Brave New World” from 1932. In it, Huxley depicts a technologically advanced world where humans are genetically engineered in laboratories, brought to life in large hatcheries, flown around in personal helicopters, and are supplied side-effect free drugs from the government to remain happy and free from pain or anxiety.

Huxley’s vivid descriptions of technological leaps and their dark consequences are just as relevant today as they were then. But when I first read the book fifteen or so years ago, I remember taking just as much notice of the elements of Huxley’s future that didn’t seem to have advanced at all. Like the elevators still having human operators.

It might seem weird that the same mind that in 1932 envisioned antidepressants, drone-taxis and synthetic biological life still kept human operators for elevators. But it really isn’t.

It’s much the same bias we all have when extrapolating technological trends into the future. We can easily imagine AI autonomously operating all the world’s cars in perfect symphony, but simultaneously struggle to envision how our own job could ever be taken by machines. We can’t have a robot pushing elevator buttons or opening doors, right? That would be too costly. I am safe!

The reason this is difficult to imagine is that AI won’t directly come after most of our jobs. Instead, AI will come for the system these jobs belong to. Enabling redesigns that might change, or even eliminate, the need for jobs we take for granted today. Our real elevator operators were victims of just this type of shift, where a system redesign made them superfluous.

To better prepare for what is ahead we should stop asking “will an AI take my job” and instead take a step back and think about how AI might affect the system that nests our jobs, and then think about the jobs we take for granted in light of these changes.

Modes of working

A natural place to start unpacking the impact of AI on work is with the word “work” itself. Simply defined, “work” means to perform an activity that involves mental or physical effort in order to achieve something.

The most basic way to work is to perform an activity solely on your own, like solving a problem in your head or fixing something with your hands. We can call this mode of work Solo Working.

A more sophisticated mode of work is to use tools. Even before humans were humans, we figured out that using tools could amplify our innate capabilities. Then rocks and sticks, now digital applications. We can call this mode of work Tool Working.

A third distinctively human way to work is to collaborate with others. Humans are social beings, and collaboration falls naturally to us. Whether in highly interdependent groups, or in looser collaborative constellations. In any case, we can call this mode of work Team Work.

So what then about AI in this context? AI is a technology, so maybe it’s just another type of tool work? But AI is also something we can collaborate and communicate with, much as we do with other humans. Maybe it’s more a type of team work then? Or can it be both?

Enter AI work

AI work doesn’t neatly fit into any of our existing categories, so let us instead treat it as the new kid on the work mode block. A fourth work mode category alongside Solo, Tool and Team work.

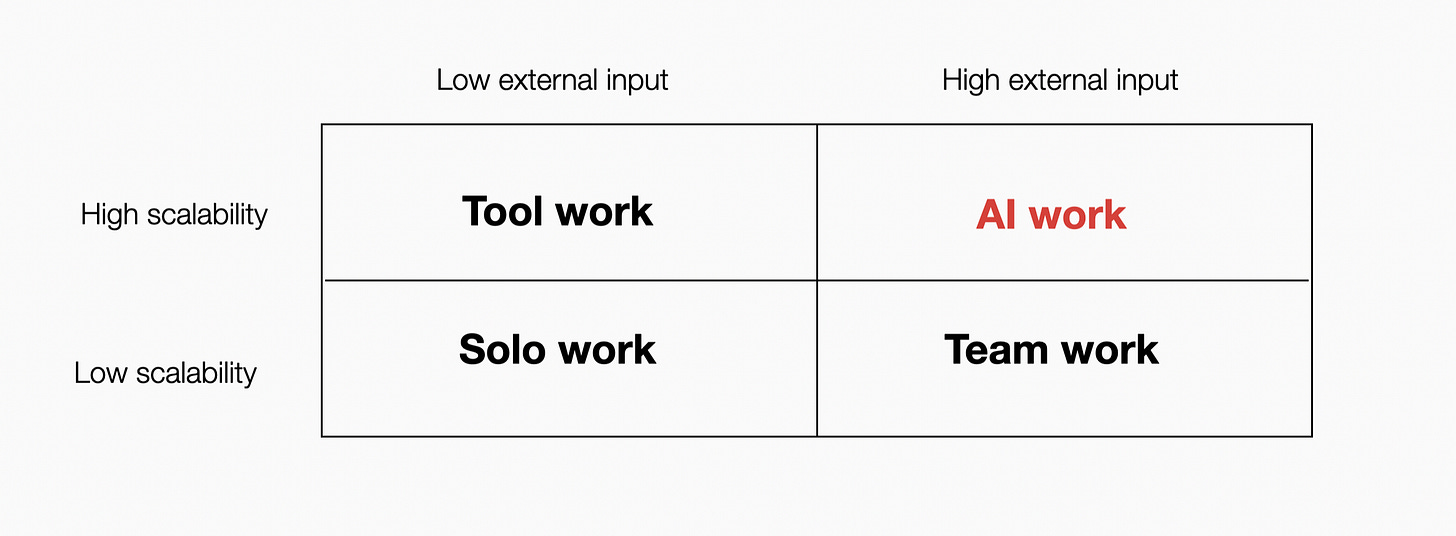

There are many ways we could organize these work modes, but here I’ll zoom in on differences along two key dimensions.

The first is scalability. Solo work is limited by personal capacity, while team work is limited with coordination complexity as the number of team mates grow. Tool and AI work, by contrast, do not have the same scale restrictions. Digital tools can process massive datasets and distribute outputs at near-zero marginal cost. AI work goes further, combining the scalability of digital tools with the ability to orchestrate collaborative workflows across tools in ways that normally would require humans.

The second dimension is the presence of external input. This can be insights, knowledge, and problem-solving approaches coming from beyond your own thinking. Solo work and tool work rely on your own cognitive resources. The data in your head or Excel might be external, but the thinking is on you. In contrast, team work brings in external input from the different skills, experiences and perspectives of your collaborators, while AI work brings in external input from patterns extracted from vast training data.

Combined, these two dimensions give us a simple 2x2 matrix that maps out key differences between the four work modes:

This work mode matrix seems simplistic, and it is. Still, it highlights something we often forget: AI work is just another mode of work.

There is nothing in this matrix, or in the discussion preceding it, suggesting that AI work or any of the other work modes are universally better. They are just different ways of performing activities to achieve something. For one purpose one mode might be better, for another purpose a different mode might be better.

But more interesting is that any task, process or role consist of different combinations of these work modes. Before, they were combinations of the original three. Now, these combinations more often also involve AI work.

Seen this way, the question of how AI will impact work becomes a question of how the introduction of AI will change the composition of work modes that goes into the tasks, roles and organizations of tomorrow.

To illustrate how this can pan out in practice, let’s have a look at how the composition of my own work modes have changed over the last 2-3 years.

Work mode recombination in practice

As a professor, I am expected to spend most of my time on research and on teaching.

Before the GenAI boom, I carried out the main tasks within these areas much as you would expect. I did maybe 1/3 solo work (creative thinking and reading), 1/3 tool work (writing, crafting slides, analyzing data) and the remaining 1/3 on team work (planning, feedbacking, writing papers with colleagues, collaborating on teaching).

Fast forward till today, the first thing I note is that the relative and absolute impact of AI on my work mode composition are distinctively different.

In relative terms, AI work has snuck in as a new work mode I use everyday, for a broad range of tasks. Since I now have four work modes instead of three, each mode represents a smaller share of my total time than before. Say from 1/3 each to maybe 1/4 each.

In absolute hours worked in the different modes, I don’t see the same drop. The reason is that AI work has created capacity that I’ve filled with more of almost everything else.

When an idea strikes while walking the dog or sit on the bus, I might quickly capture it with AI, explore it deeper, test different angles, and check if it holds up. Ideas that before would end up as a short note on my phone or as a sentence in my notebook, now often gets developed much further on the fly.

This better capture, documentation and quick exploration of ideas opens them up, and invite deeper and more elaborate thinking. I have more ideas than before, and each is richer with higher resolution. The result is that I end up spending more time with solo work, like thinking more on work related ideas on dog walks and on bus rides than before.

This extended thinking about ideas then leads to more writing (tool work), as I like to get my thinking sanity-tested on paper. This I have always done, but now that my personal AI-editor can help me out with even the roughest draft, the writers block has been obliterated.

So what about team work? Has AI replaced that then?

Not quite. But it has sure changed it. Before, I quickly turned to colleagues to discuss early ideas or get feedback on rough drafts. Less so now that I have a feedback machine that patiently listen and enthusiastically discuss my ideas whenever I want. Always available. Never tired. Never bored. I still turn to my colleagues with ideas and drafts, but often much later in a process than before. And in different ways.

So, for me, the efficiency gains from AI work has created capacity that let me spend more time in solo thinking, more time writing in my notebook or on my Mac, and more time discussing elaborate ideas with peers. And it has fundamentally changed how I combine the different work modes to deliver much the same type of output as before. With the result that I am now both more creative and productive than earlier.

Have i AI-proofed my job then?

Not necessarily. Because while I was busy rethinking my own work modes with AI, others were busy redesigning the entire system my job exists within.

System redesign: The other force at play

This brings us back to our elevator operator. We could study that guy all day, give him Microsoft Copilot to improve his efficiency and quality of work, and he might recombine his work modes for the better as a result. Just like I did. But that wouldn’t help if engineers redesign entire elevator systems to eliminate the need for any operators. Whether they have copilot or not.

The same dynamic is currently brewing across knowledge work more generally because of AI.

Take research, which is a core part of my job. While I’ve been recombining my work modes to be more creative and productive in writing and coming up with new ideas for research, companies like Google’s DeepMind have been building AI systems that can conduct scientific research end-to-end. Their co-scientist agent can formulate hypotheses, design experiments, analyze results, and even write up findings. Potentially replacing entire research workflows as we know them today.

Or consider teaching, my other major responsibility. While I’ve been using AI creatively to push the thinking that goes into my own teaching, companies like Curipod and Sana Labs are building systems that can automatically generate complete lesson plans, activities, and assessments for teachers or businesses. While their value propositions today are to help teachers plan better, these efforts are essentially redesigns of what teaching preparation looks like entirely. Tomorrow these plans and materials might go straight to the learners, eliminating workflows where we take for granted that a professor or instructor should have a role.

This push for system redesign is not happening by accident. It happens because the true benefits of AI work’s scalability combined with high external input happens at systems level. While I enjoy some benefits of AI’s scalability, like having multiple agents researching a topic for me simultaneously, it’s nothing compared to what’s possible at a systems level. Millions of teaching agents could personally tutor individuals, and thousands of research agents lead by a handful of scientists could develop hypotheses, review previous research, collect data, run experiments, and write up the results.

At a systems level, AI is not just replacing individual work modes. It’s allowing us to do things that would never have been possible until now, at a scale. Like one bright professor simultaneously tutoring thousands at a time in a deeply personalized way, free from human limitations. Or a top researcher orchestrating thousands of research agents to support her work. With the potential consequences that many workflows, tasks and jobs we take for granted becomes less valuable than before.

This begs the question: Am I also an elevator operator?

The strategic challenge

The uncomfortable answer is that we all might be. Because AI-driven changes will be more than just individual efficiency improvements. They are system-level redesigns in the making that over time might change the fundamental logic of human involvement in many areas of work.

The two different forces at play, the individual changes in work mode compositions and the redesign of the very systems that organize these jobs, make it difficult to assess how the jobs of today are affected by AI tomorrow. Especially if we only focus our attention to one of them.

Because just as we couldn’t understand the future of elevator operators by studying elevator operators, we can’t understand the future of professors by only studying how they rethink their own work with AI. Instead, we need to evaluate what the system itself may create with new capabilities, relative to what humans can create with their recombined work modes.

Maybe the professor of tomorrow finds its place by focusing more on what is uniquely human and idiosyncratic. Like sharing a particular perspective on the world, or coming up with novel ideas grounded in unique experiences. Or maybe the professor of tomorrow is a middle manager of AI agents doing research and teaching at scale. Or maybe both. Or neither.

The elevator in Huxley’s Brave New World could in fact run itself. The elevator operator was there by design. For the “low-caste semi-moron” workers to have something to do. Pushing buttons and opening the door on command from the voice of the elevator. Which is yet another potential future for many of us. Carrying out work for the AI, instead of the other way around.

All this is of course lofty speculation, but I will be surprised if the role of the professor tomorrow is the same as it is today. Just like I will be surprised if many other roles in the knowledge economy don’t look different tomorrow.

Why this matters

The value of thinking of AI as a new work mode is not in the framework itself. It’s in reframing the question from “will AI take my job?” to “which combinations of work remain valuable as systems redesign themselves around us?”

We are all in a sense potential elevator operators now. Relying on Copilot or ChatGPT to improve our button-pushing craft in our elevators, while engineers are elsewhere seeking to redesign the entire system. But unlike those original operators, we could see it coming. If we are looking at the right things.

Not all AI work is the same. Some amplifies thinking, others amplify doing. Some extends our impact, others replace it. Some AI work is more resilient to system redesigns, others less so. Understanding these distinctions seems important.

Because in the end, no one wants to be the one who diligently perfected their workflow with AI right up until the day they were not needed anymore.

Excellent (and unsettling) 👍