M.005 Strategy, Business Models, and the Solar System

Sometimes the best way to understand something is through its relationships to other things.

You are reading Molekyl, finally unfinished thinking on strategy, creativity and technology. Subscribe here to get new posts in your inbox.

When I’m teaching executives on strategy and business models, I often start with the solar system. Or more precisely, I ask them to define what a moon is.

Most start with properties: “it's round, made of rock and dust, has no atmosphere, orbits around Earth”. But then someone notices that moons come in different shapes and sizes, with different properties, and that other planets have moons too. Gradually, the definition shifts to something more fundamental: a moon is simply a celestial body that orbits a planet.

Then I ask the executives to redo the exercise and define a planet. Again, they suggest properties like size, atmosphere, or composition. And again, this doesn't quite capture it. After some discussions, the conclusion tends to be that a planet is a celestial object (of a certain size - we all remember what happened to Pluto) that orbits a star.

Finally, we move to define a star, which goes faster: it's a luminous celestial body with orbiting planets.

The point of this exercise is twofold. First, to reveal that sometimes the best way to understand something is through its relationships to other things. A moon wouldn't be a moon without a planet to orbit, and a planet wouldn't be a planet without a star to orbit.

The second point is to set up an argument. Namely that the same relational logic that clarifies celestial bodies, might be very useful to untangle some of strategy's most confusing concepts.

From stars to strategy

Strategy is full of concepts. Definitions of individual concepts tends to make sense seen in isolation, but overlaps and unclear distinction between them often confuse people. Because what is really the difference between a strategy and business model, and how do the two concepts relate? And what about value theories in all of this?

I think the same logic that helped us define moons, planets and stars provide an elegantly simple yet powerful answer to these questions. That is, instead of trying to precisely define each strategy concept by studying it in detail, we can think about these concepts like our celestial bodies and define them through their relationships to each other.

To give it a go, let's start with strategy’s equivalent of a star - the value theory (a.k.a corporate theories). A value theory is an abstract idea in the form of "a logic that managers repeatedly use to identify from among a vast array of possible asset, activity, and resource combinations those complementary bundles that are likely to be value creating for the firm." (Zenger, 2016). Or in simpler terms, it is the fundamental belief system about how your company can create value.

Just as a star provides the gravitational center of a solar system, a value theory provides the fundamental beliefs and logic that guide a company's search for value-creating opportunities and strategies. The value theory is often implicit, but it's always there. Whether you like it or not.

Next we have the equivalent of a planet, the strategy orbiting around the value theory. A strategy is an overarching and concise description of how a firm intends to create and capture value to reach its goals. A strategy is also overarching, but relatively more concrete on the how, the what and the why than the theory. Usually, a well crafted strategy clarifies a firm’s key hypotheses around goals, customers, offerings, value propositions, as well as key hypotheses of how the firm believes their activities and resources will lead them to create and capture more value than competitors.

Just as planets take concrete form while following their star's gravitational influence, strategies make value theories actionable while staying true to their guiding logic.

Finally, business models are our moons. A business model details the actual machinery of value creation, value capture and value delivery, and is thus more concrete than the more general treatment in the strategy. It describes the key elements that follows from the strategy, how they connect, their causality and the complementarities that make everything work together. It's in the business model that the abstract value theories and overarching strategic hypotheses meet operational reality.

Just as a moon orbits a planet, a business model explicate and operationalize a strategy by translating overarching hypotheses into a sophisticated description of the machinery aimed at creating, delivering and capturing value.

It's a system, and a hierarchy

From these relative relations we see that a hierarch emerges. The most abstract and overarching layer is the value theory. While value theories often remain implicit, they can be explicated and condensed into a simple if-then formulation in a sentence or two. Then comes the strategy. While still quite abstract, it brings more details of the what, how and why of key decisions the firm should make to achieve it's goals. Finally, the business model provide more elaborate descriptions of how firms operate and operationalize the strategy.

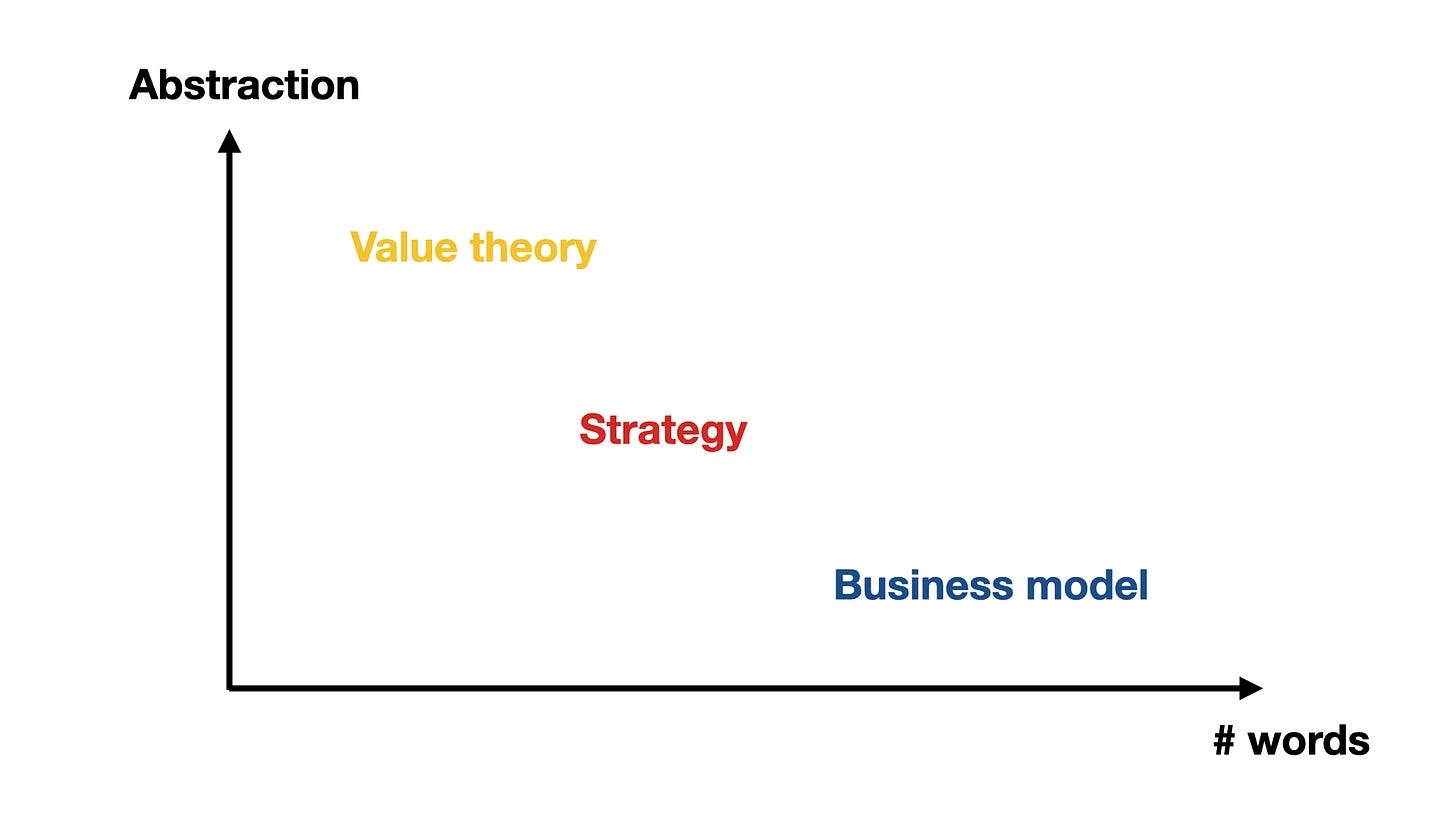

From this, we can map out the different concepts along two dimensions. The number of words (the details), and their level of abstraction. As shown in the figure below.

But more than being a simple framing, this laid out logic also reveals some important implications for strategy.

First, as we move from theory to business model, we increase in detail but decrease in abstraction. A value theory might be expressed in a few powerful sentences. A strategy can be condensed to half a page to a page. While a business model might require pages of documentation to fully describe.

If your strategy is document is 30 pages long, brimmed with details about the operational choices that will lead your company to win, it might be better to call it a business model. And write out a more overarching strategy instead. If your strategy is a line or two depicting what you think is important to succeed, call it a value theory and detail a strategy that follows from this.

Second, just as multiple planets can orbit the same star, and multiple moons can orbit the same planet, different alternate operationalization of the level above can make sense at each level. One strategic theory might support several viable strategies, and each strategy might be executed through various business models.

But this hierarchy isn't just an academic exercise. It can have a strong practical relevance through determining where you should focus when things aren't working as planned. If a firm struggle, is the problem it's business model, it's strategy or the value theory itself? Without a conceptual understanding of these levels, it's easier to reject a good idea on the wrong grounds. For example to reject a value theory or strategy, when it really was the business model that should be changed.

Third, changes can flow in both directions - just as gravitational forces work in multiple ways. A new theory might lead to new strategies and business models (top-down), and changes in a business model might lead to updates to strategy and even the overarching theory (bottom-up).

So while strategy is very much a top level responsibility, acknowledging that strategic change and innovation input might also flow from below will make you more open to new insights, ideas and learning.

Fourth and finally, alignment matters. Just as moons don't exist without planets to orbit, and planets don't exist without stars, business models make most sense when they align with strategy and value theory. Just think of Tesla: their value theory (sustainable transport through vertical integration) guides their strategy (premium electric vehicles with proprietary charging), which shapes their business model (direct sales, supercharger network, software updates).

A business model that doesn't align with strategy is, on the other hand, like a moon trying to orbit the sun directly. It might work for a while, but it's probably not stable. Because when alignment fails and business models drift from strategy, or strategies ignore the guiding theory, coherence and alignment suffer. Then companies become collections of activities rather than unified value-creation machines. And they become less likely to reach their goals.

Final words

I believe the that the power of this simple framework lies in its simplicity. It can help avoid getting lost in endless debates about definitions, and allow us to instead focus on what matters more: to understanding how these concepts relate and work together.

So the next time someone asks you to define a business model, a strategy or a value theory, don't start with its properties. Start with its relationships. Because it might just save you from getting lost in space.